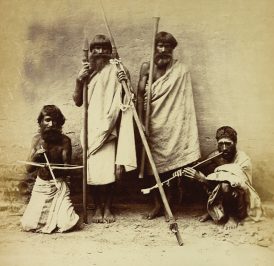

In the latter half of the second millennium BCE, networks of trade and exchange developed throughout South Asia. Urban polities thrived on the extraction of upland forest products, feeding them into networks across the region, the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Forest products included plant materials and animal by-products – such as timber, medicinal plants, dyes, resins, furs, skins, bones, and ivory – as well as metal ores and gemstones. Forest-dwellers, with their ecological knowledge, became key suppliers in the urban economies of Asia. In the early nineteenth century, the British colonial enterprise started to ‘legally’ appropriate forested land from indigenous owners, relegating them to a subaltern role in the global economy of the following centuries.

Today, Indian upland forest-dwellers – like many other indigenous communities around the globe – are currently under threat from resource extraction, agricultural development and de-forestation as are the material remains of their cultures. Indian forest-dwelling communities are still perceived as a-historical, the geschichtslosen Völker of nineteenth century historiography, therefore research on their past is scant and inadequate. This is the result of a Eurocentric perspective that is still dominant today and relegates Indian upland forest-dwellers to the margins of history. The aim of the Nilgiri Archaeological Project is to change this view and develop a new interdisciplinary framework to study the pre-colonial history of Indian upland forest-dwellers. To this end, our research combines the theories of Subaltern Studies with those of environmental history, and integrate the methods of landscape and environmental archaeology, material culture studies, palaeoecology and ethnobotany, ethnohistory and textual analysis. The Nilgiri Archaeological Project investigates the built and natural landscape, museum collections, archaeobotanical remains, early colonial herbaria and botanical literature, oral histories, inscriptions in Old Kannada, and Caṅkam literature and Tamil epics.

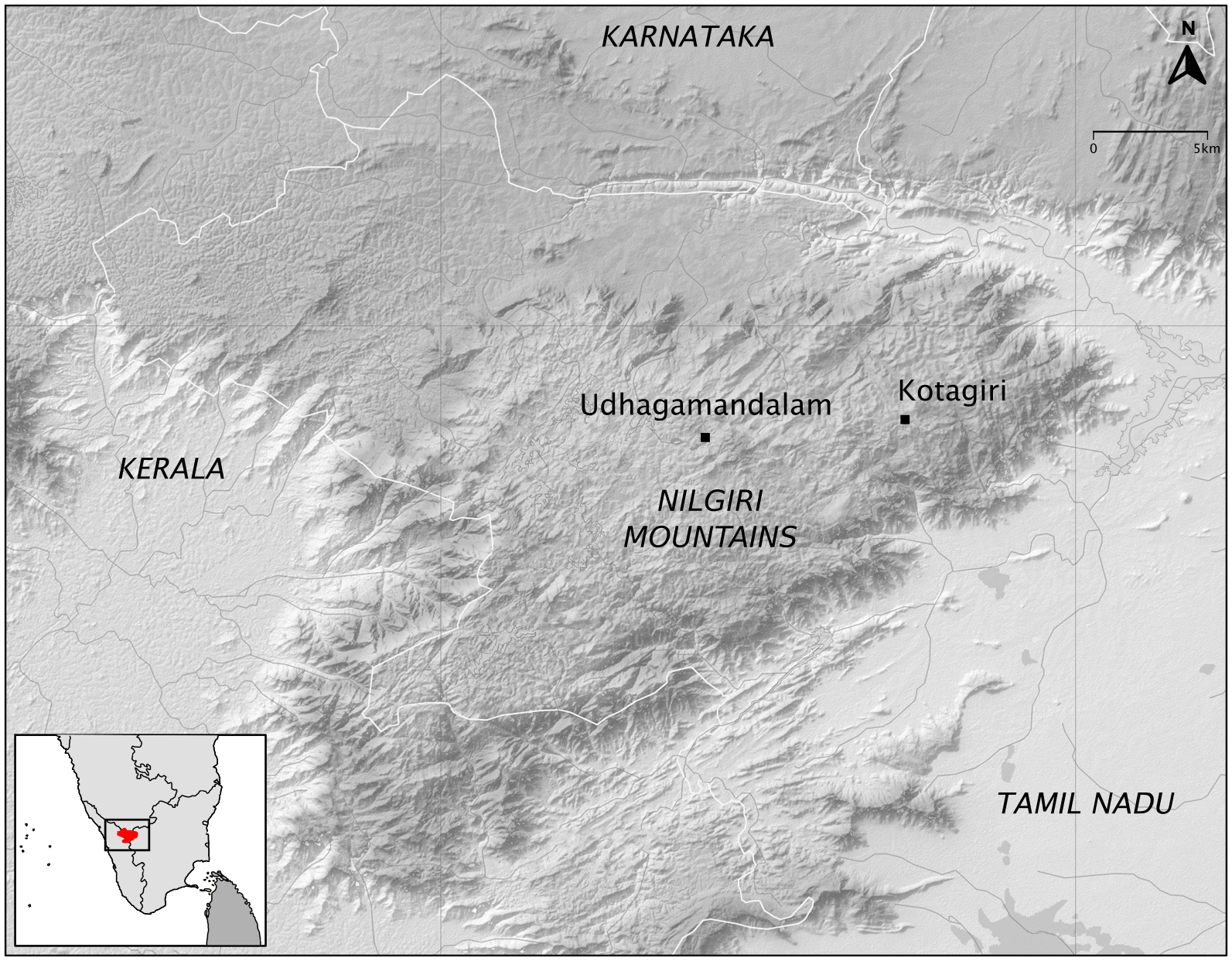

Our research focuses on the Nilgiri Mountains in southern India, a massif of some 2400 km² forming part of the Western Ghats mountain range. This is a region of montane subtropical forests with peaks over 2500 m. The area is the homeland of – at least – sixteen ethnic groups, which practice gathering and trading of forest products, swidden agriculture, pastoralism, and wage labour. The Nilgiri region has been selected because of the unique richness of excavated assemblages and structural remains. The chronological horizon of the Nilgiri Archaeological Project runs from the start of the Common Era to the early nineteenth century. According to limited archaeological and palaeoecological evidence, occupation of the Western Ghats started around the first century CE, when the demand for forest products – mainly black pepper and cardamom – increased due to flourishing Indo-Roman trade. In 1835, the British established the first tea plantation in the Nilgiris, which was followed by many others. This profoundly affected the ecology of the region. The chronological limits of our project are therefore drawn by these two key interventions in the landscape.

In order to achieve the project’s aim, the Nilgiri Archaeological Project interrogates four datasets, each of which addresses a specific research question.

Built and Natural Environment

To what extent did the forest-dwellers of the Nilgiri Mountains communities adapt to, transform, and exploit the forested environment?

The tops and ridges of the Nilgiri Monuntains are dotted with one or – more often – a group of megalithic tombs, which were excavated, in the 19th century, by British colonial officials, who also documented non-burial funerary monuments – such as dolmens and memorial stones. In order to answer the first research question, we will map the sites of burial and non-burial monuments of the area north of the towns of Udhagamandalam and Kotagiri (roughly 60 km²), where most of excavated burial sites concentrate, to reconstruct the funerary landscape of the region. Site distribution will then be analysed to determine

patterns of occupation and define the relation between burial and non-burial sites as well as between these sites and the surrounding environment. Landscape features that can lead to the identification of settlements will be given special attention since the settlements associated with the funerary monuments of the Nilgiri Mountains have never been discovered.

We will also collect pollen and phytolith samples to reconstruct the early ecology of the study area. The newly collected samples will enlarge the collection of pollens and phytoliths from the Nilgiri forests of the French Institute of Pondicherry, one of the largest in India, which is linked to its own herbarium and to others around the world.

Museum Collections

What was the perception that the upland forest communities of the Nilgiri Mountains had of themselves and the world around them?

Museum collections of Nilgiri grave goods excavated from megalithic burials in the nineteenth century offer a unique opportunity to analyse a large assemblage of archaeological artefacts unearthed in an Indian region of upland forests. Grave goods are the only excavated evidence we have of the past Nilgiri forest-dwellers since

settlements have never been discovered. The Nilgiri burial assemblages include ceramics, and terracotta, bronze, iron, gold and stone artefacts. The largest collection of Nilgiri grave goods is at the British Museum, another substantial collection is at the Government Museum in Chennai, while a small collection of terracotta figurines and potsherds is at the Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin.

Given the importance of the study of funerary practices and burial assemblages in recovering the identity of the deceased and their community, in order to answer the second research question, we will carry out a comprehensive and systematic study of the museum collections of Nilgiri grave goods to establish a relative and absolute chronology of the grave goods from the Nilgiri Mountains, identify their findspots, reconstruct burial assemblages, and determine the source of imported items and the likely routes by which they came to the Nilgiris. In combination with the analysis of grave goods, we will also carry out an iconographical study of the reliefs sculpted on the memorial stones.

Written Texts and Oral Histories

What do inscriptions in Old Kannada and literature in Old Tamil as well as contemporary oral histories of the forest-dwellers of the Nilgiri Mountains reveal of past upland-lowland interactions?

The earliest historical record mentioning the Nilgiri region and its inhabitants is a stone inscription in Old Kannada found in the Pārśvanātha Jain temple at Chāmarājanagara in Karnataka dated to 1117 CE. Copper-plates and stone inscriptions of the twelfth century found in the lowlands surrounding the Nilgiris attest the use of Old Kannada and are evidence that this language served as a lingua franca in the upland areas.

Caṅkam literature is a corpus of Old Tamil texts, which is regarded as the classical literature of South India. It is dated ca. 100 BCE-250 CE and comprises anthologies of poems, which are classified into seven genres or tiṇais, each linked to a specific landscape; the kuṟiñci tiṇai sets its poems in a forested upland landscape. Tamil epics such as the Cilappatikāram (fifth century CE) and the Cīvakacintāmaṇi (tenth century CE) also contain chapters on the forests and the forest-dwellers.

The forest-dwellers of the Nilgiri Mountains speak Dravidian languages and dialects, and have a rich oral literary tradition: folktales, songs, and prayers.

In order to answer the third research question, we will analyse texts in Old Kannada and Old Tamil to reveal information about past upland-lowland relations, and understand how forests and forest-dwellers were perceived by South Indian urban societies and how the otherness of the forest-dwellers is constructed in external textual sources. We will then comparatively study the oral literature produced by the indigenous communities of the Nilgiri Mountains to reveal information on past upland-lowland relations and understand how the otherness of lowland people is constructed in these texts.

Early Colonial Botanical Literature and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

What was the knowledge of the forested ecosystem that the indigenous communities inhabiting the forests of the Western Ghats had?

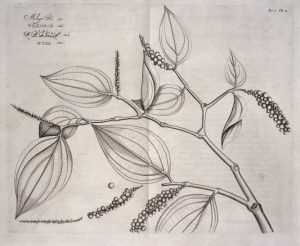

The Hortus Indicus Malabaricus (1678-1693), an illustrated treatise on the flora of the Western Ghats (the mountain range including the Nilgiri massif), has been considered the key text on Indian botany for centuries.